The Story of Albanian Movie Posters

Until a few weeks ago, I've never seen an Albanian movie poster. That, luckily, changed after a small exhibition in Zagreb, a part of the Film Mutation Festival. Those eight hand-drawn posters on the movie theater's lobby wall made quite an impression on me and I felt that I saw just a the tip of an iceberg, one I was anxious to explore. The only problem was—Google knew next to nothing about Albanian movie posters.

Poster exhibition in cinema Europa, Zagreb in January 2018 (foto by Nina Đurđević)

Turns out, the man responsible for the exhibition, Thomas Logoreci—an Albanian-American filmmaker—was the best clue I could have found. In April 2016, he curated a big exhibition in The National Gallery of Arts in Tirana, showing hundreds of movie posters from Albania's glory cinema days, saving them from oblivion. The attendance was so high it had to be extended for another few months. The exhibition's catalog (the only existing publication on the topic to this day) served as a valuable source of information and images, as did Thomas himself, readily answering all my questions.

Of course, the story of poster art is inseparable from Albanian history in the 20th century, so what follows is a short overview with focus on the dictatorial regime from 1944 to 1991.

History of Albanian cinema

At the end of World War II, in November of 1944, communists took control of the country as the German troops withdrew. Soon after, People’s Republic of Albania was formed, led by Enver Hoxha and the Labour Party of Albania. Denouncing most Eastern European socialist countries as revisionists, Albania maintained a strict observance of Hoxha’s own brand of socialist realism, with self-isolation determined as the only way to successfully implement it.

Kinostudio "New Albania"

founded in 1952 by the dictator Enver Hoxha with the initial support of the Soviet Union.

The next 47 years were traumatic in many ways, but cinema—always a powerful propaganda tool—was booming. Soviet-built Kinostudio 'New Albania' opened in Tirana in 1952, and in the next 39 years produced 232 fiction features, thousands of documentaries, newsreels and animated films. At that time owning a TV was a luxury, so attendance of 450 Albanian indoor and outdoor movie theaters was counted in millions. One person attended an average of ten films per year—in a grim reality, cinema was a welcome distraction. At the same time, foreign influences on Albanian cinema ware extremely limited—the only films that could be shown were productions by the Soviet Union and China. Interestingly, a number of Albanian films were also regularly screened in China, gaining big success and popularity.

A still from Tomka dhe shokët e tij/Tomka and his friends (1977).

A booming industry needs its workforce, so students were allowed to study film-making in like-minded regimes of Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union. That soon brought Albania her first movie directors, along with a new wave of actors and actresses. Results came quickly: the first New Albania fiction feature Scandeberg (a historic epic about the 14th century warrior who held off the Turkish occupation until his death) went on to win a prize at the Cannes film festival in 1954.

“For some, the moving images from the Kinostudio era are a painful reminder of a closed society where watching a foreign film on television could result in a prison sentence for being under the influence of ‘foreign powers and propaganda’.”

Cinematic output kept increasing in the following decades with varying levels of regime influences. Two dramas—A Tale from the Past (1987) and Strings for a Violin (1988), produced after Hoxha's death in 1985, signaled a move towards individual-based themes, something unthinkable of years before.

The regime eventually came to an end. "New Albania" didn't survive the transition to democracy and closed its door in 1991, leaving filmmakers without work and reducing cinema production to a trickle. Since then, Albania's cinema output counts around half a dozen of films annually, mainly copies of Western-genres, while theaters (and audiences) prefer Hollywood production. This is something I can easily relate to living in Croatia (a country that shares a similar history with Albania).

Although many people reject their cinematic history today as one long ideological indoctrination, films from that period became part of the collective memory of Albanians. They are also a valuable material for scholars and filmmakers trying to understand how authoritarian regimes wield power.

Poster art

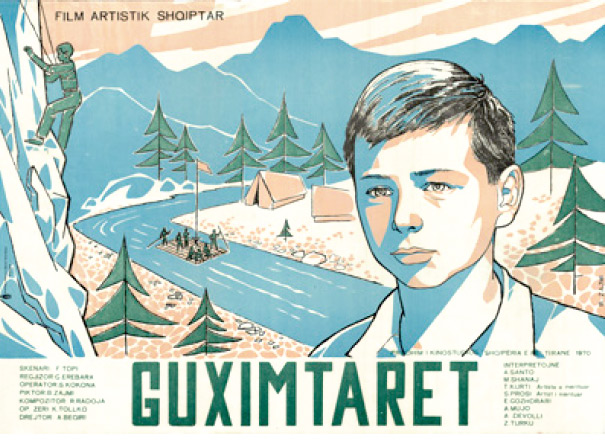

A fortunate outcome of the closed regime are neatly organized film archives, which include film stills, press books, musical scores and posters. Upon the anticipated release of a motion picture, the film's production designer was enlisted to create unique poster art. The classic subjects these posters dealt with were good triumphing over evil, heroic anti-fascist war, economic reconstruction, ridiculing old ways of living and love stories in a socialist-realist key.

'Tana' (1958), designed by Namik Prizreni

Like movies, poster art was also shaped by the regime: examined of any unwanted subliminal messages, they had to be painted in a photo-realist, figurative style—portraits of main characters were a must. While Polish and Cuban posters we know from this era are often abstract and full of symbolism, this offers an explanation why that wasn’t the case in Albania. Still, these gifted artists managed to make the best of the situation and visualize movies in a creative, eye-catching way, with vividly colored illustrations and creative typography. Apart from their artistic merits, it's hard to look at these hand-made images today and not feel nostalgic for some distant times.

Guximtarët/The Brave Ones (1970) designed by Bujar Zajmi

Kur zbardhi një ditë/Once at Dawn (1971) designed by Mariana Eski

A short period of liberalization in culture that happened between 1968 and 1973 brought more impressionistic and subjective posters that borrowed a lot from Italian and French cinema design, along with elements of Russian Constructivism (posters for Odiseja e tifozave and Horizonte te hapura are good examples of this).

Horizonte te hapura/Open Horizons (1968) designed by Shyqyri Sako and Odiseja e tifozave/ (1972)

“ I am kind of obsessed with Albanian films but as we began going through the archive, preparing the show, I began to realize I had never seen most of these designs before. Neither, it seems, had the Albanian public.”

Some of the most notable artists from that era were: Sali Allmuça, Arben Basha, Ksenofon Dilo, Myrteza Fushekati, Grigor Ikonomi, Azis Karalliu, Bujar Luca, Kleo Nini, Namik Prizreni, Alush Shima, Dhimitër Theodhori, Astrit Tota, Ilia Xhokaxhi and Shyqyri Sako. Three of them—Azis Karalliu, Kleo Nini and Shyqyri Sako—managed to visit the 2016 exhibition in Tirana, with Mr. Sako even sharing a several anecdotes about the making of posters and hurdles with the censorship.

Times have changed and it probably comes as no surprise that posters in Albania are no longer made the same way—designers now replicate Hollywood, using film stills as main visuals, trying to get audiences in theaters. I guess free market is a regime with its own rules. A nice exception came with Bota, a 2014 film by Thomas Logoreci and Iris Elezi (recently named director of Albania's national film archive where all the original posters are held today). It used a painted poster as an homage to the Kinostudio era (specifically to the artist Shyqyri Sako)— a suitable approach since Bota deals with the historical legacy of Albania under the communist dictatorship. The best compliment for the poster came at the movies's premiere in Karlovy Vary when copies of the poster were stolen from the theater walls within hours after putting them up.

Bota (2014) designed by Eklind Vejsiu

Polish posters have grown into a huge business these last few decades. Cuban posters are getting more and more popular each day with books written about them. Even crazy posters from Ghana appear regularly all over the Internet. But one small East-European country and its culture remains largely unknown to this day, even two and a half decades after the fall of its strict one-party communist system—something it shares with Poland and Cuba, among many others. This mysteriousness fascinated young Werner Herzog so much that he walked along its closed borders by foot (never daring to enter). Living only a thousand kilometers from it, I knew very little of the country, let alone its cinema (and I wasn't as adventurous as Mr. Herzog). Turns out, Albania has a huge cinematic heritage (which is in great danger of vanishing), and posters are a big part of it. Poster exhibitions and screenings of films previously unseen by the West are a great start. Could Albania be next in line of getting a deserved recognition, becoming a significant chapter in European film history books? I think (and hope) so.

Gallery

The following posters are grouped by their author. Source: “The Art of Albanian Motion Picture Design – Highlights from the Kinostudio Years”exhibition catalog (used with kind permission by Thomas Logoreci).

Arben Basha

Nëntori i dytë/The Second November (1982)

Shirat e vjeshtës/The Autumn Rains (1984)

Astrit Tota

Ata ishin katër/They Were Four (1977)

Kërcënimi/The Threat (1981)

Dy herë mat/Twice Checkmate (1986)

Azis Karalliu

Ilegalët/The Illegals (1976)

Përballimi/Confrontation (1976)

Nusja dhe shtetrrethimi/The Bride and the Curfew (1978)

Intendenti/The Quartermaster (1981)

Në kufi të dy legjendave/On the Border Between Two Legends (1982)

Shokët/The Comrades (1982)

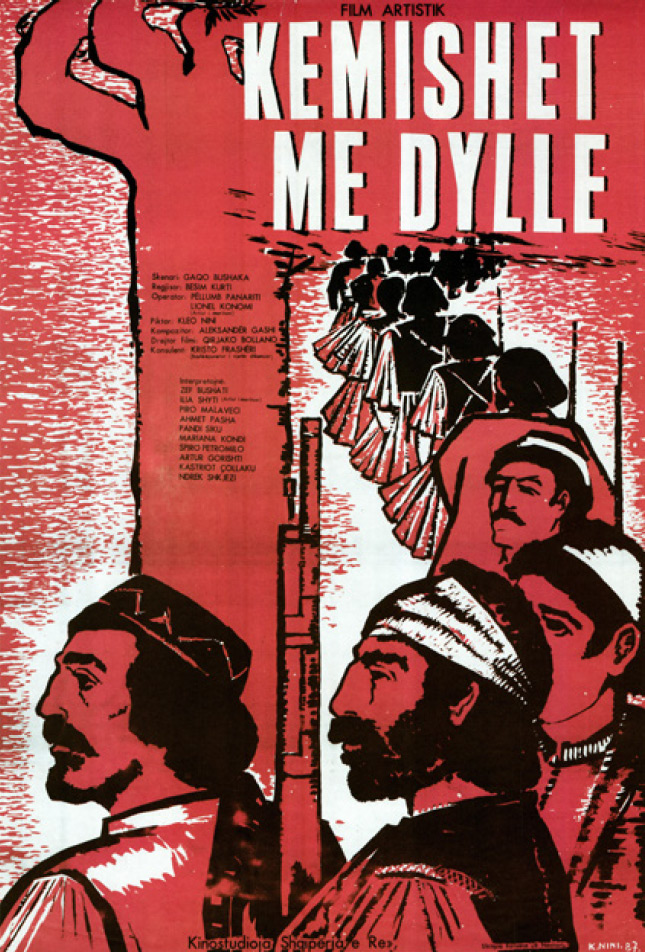

Kleo Nini

Gjurma/The Trace (1970)

Pylli i lirisë/The Forest of Freedom (1976)

Fejesa e Blertës/Blerta’s Engagement (1984)

Taulanti kërkon një motër/Taulant Wants a Sister (1984)

Këmishët me dyllë/Wax Shirts (1987)

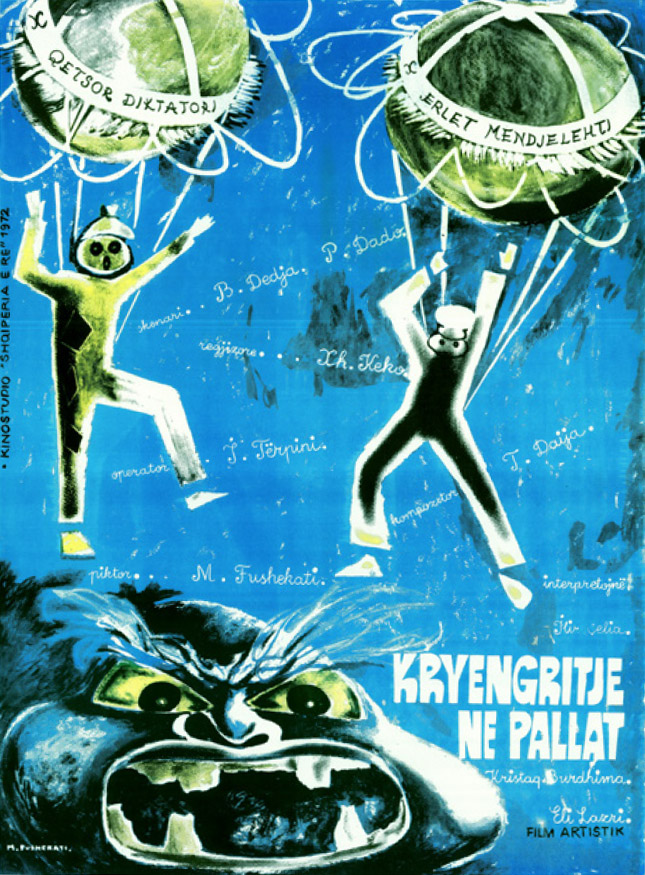

Myrteza Fushekati

Lugina e pushkatarëve/The Valley of Riflemen (1970)

Mëngjeze Lufte/War Mornings (1971)

Kryengritje në pallat/Riot in the Building (1972)

Mimoza Llastica/Mimosa, the Spoilt Child (1973)

Namik Prizreni

Fije që priten/Broken Threads (1976)

Skëterrë 43/Hell '43 (1980)

Militanti/The Militant (1984)

Shyqyri Sako

Njësiti gueril/The Guerilla Unit (1969)

Montatorja/The Fitter Girl (1970)

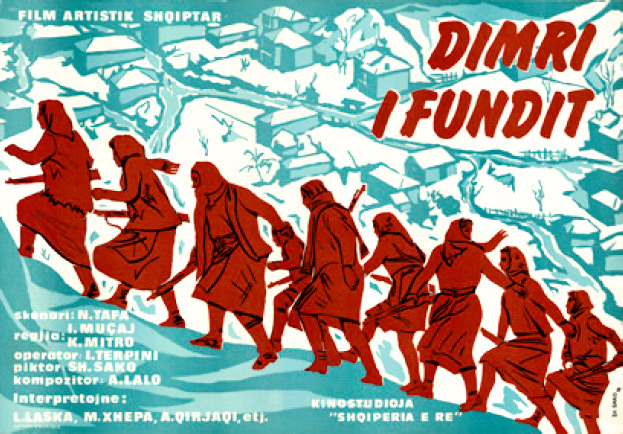

Dimri i fundit/The Last Winter (1976)

Radiostacioni/Radio Station (1979)

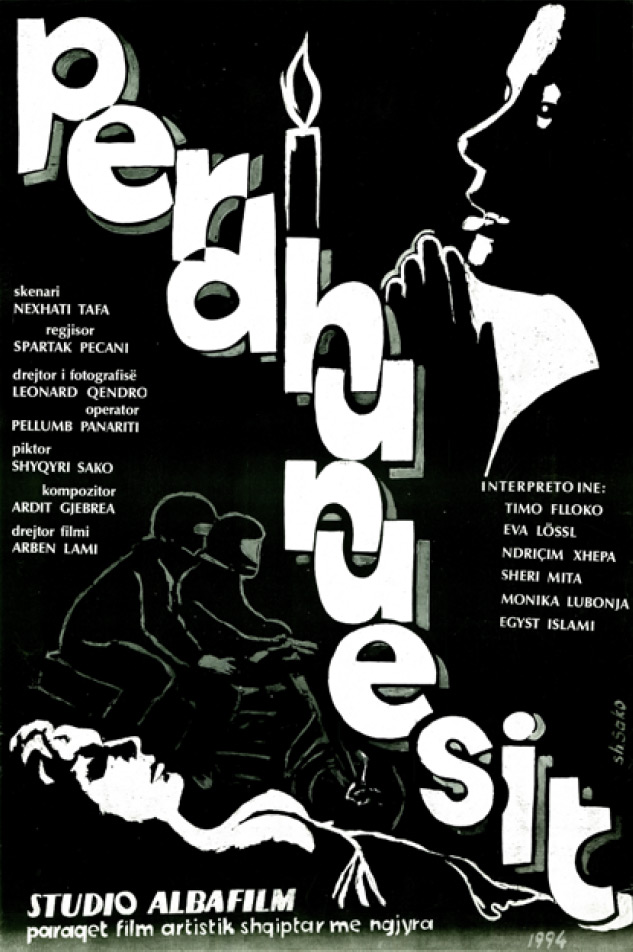

Përdhunuesit/The Rapists (1994)

Resources for further research

Unknown pleasures: lifting the lid on a treasure trove of Albanian cinema

[http://www.calvertjournal.com]Albanian Cinema Project

[www.thealbaniancinemaproject.org]Saving Albania’s Film Legacy

[www.movingimagearchivenews.org]'Here Be Dragons', documentary by Mark Cousins

[www.imdb.com]Arben Basha interview

[www.kosovotwopointzero.com]

Conversation with Thomas Logoreci and his essay for the exhibition catalog were crucial sources of information for this article. I also thank Regina Longo (Albanian Cinema Project) and Eriona Vyshka (Albanian National Film Archive) for their help.